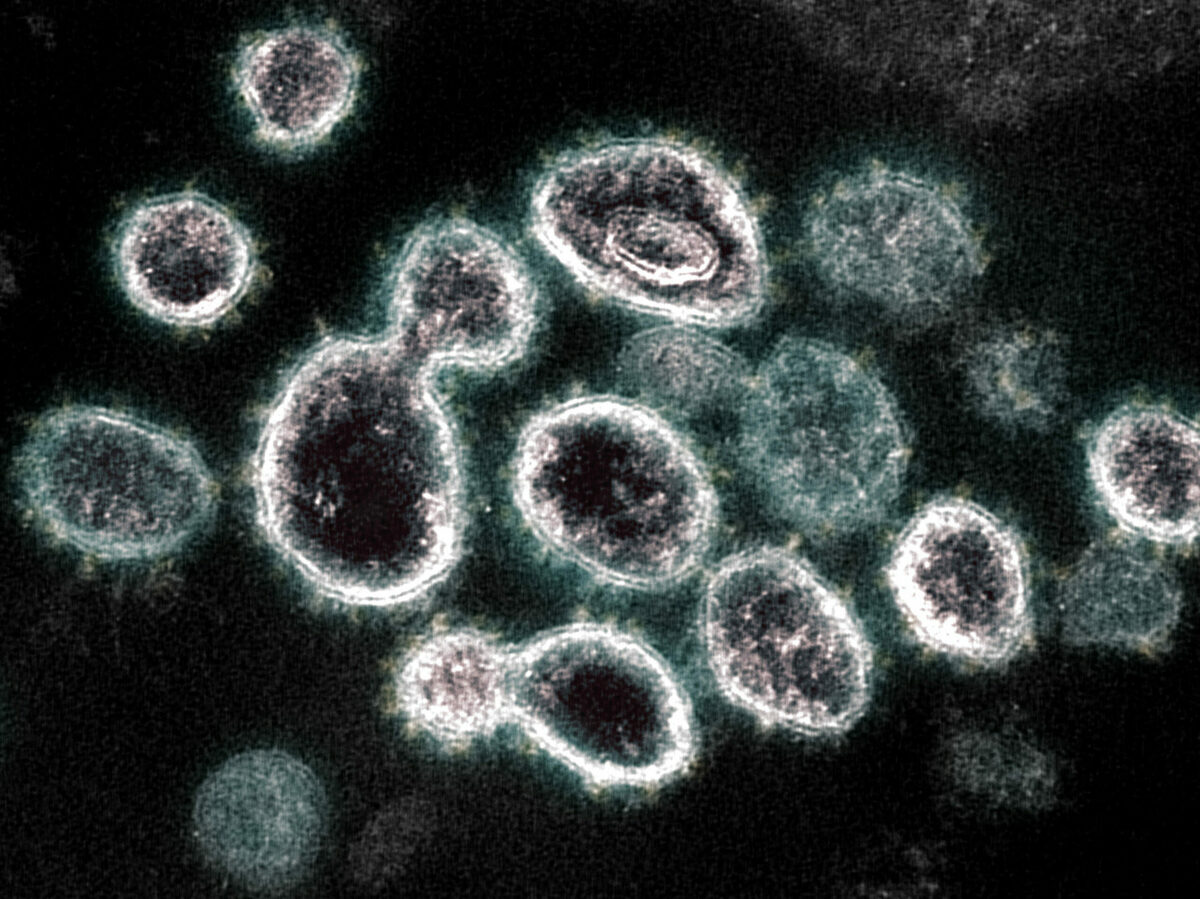

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, isolated from a patient in the U.S. BSIP/BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images hide caption

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, isolated from a patient in the U.S.

BSIP/BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesWhile the country seemingly moves on from the pandemic, an estimated 15 million U.S. adults are suffering from long COVID. Scientists are trying to understand what causes some people to develop long COVID while others do not.

NPR's Will Stone spoke with researchers and reports on a growing body of evidence that points to one possible explanation: viral reservoirs where the coronavirus can stick around in the body long after a person is initially infected.

Email us at

This episode was produced by Elena Burnett. It was edited by William Troop, Will Stone and Jane Greenhalgh. Our executive producer is Sami Yenigun.

Live Radio

Live Radio